All people deserve safety in their homes, workplaces, parks, and other community spaces—safety not only from violence, but from the economic, social, and environmental conditions that fuel violence in the first place. Within the United States, however, access to physical safety—just like access to clean air, economic mobility, and high-quality schools—is shaped by where someone lives, with many of our most unsafe places reflecting decades of systemic disinvestment.

To keep individuals, families, and communities truly safe from violence and harm, 1 policymakers must tackle the “social determinants of safety” that contribute to neighborhood violence in the first place. 2 Just as in public health, where prevention is the most effective way to keep people healthy, preventative safety is the most effective way to maintain public safety. Yet federal spending and policy priorities are not structured to harness this insight—the U.S. government dramatically underspends on programs that are most effective at improving community safety, while allocating billions to punitive programs that harm both families and communities.

The following blueprint is designed to help federal lawmakers address this mismatch by outlining an evidence-based policy agenda that prioritizes upstream interventions to advance community safety. Given widespread concerns about community violence and harm, as well as the forthcoming expiration of American Rescue Plan Act (ARP) dollars currently funding community safety interventions, it is more essential than ever that the U.S. government build sustainable, flexible, and long-term funding streams for evidence-based safety programs.

The blueprint begins with an overview of recent crime trends to provide context for thinking about violence as a place-based issue. After establishing this baseline, the blueprint highlights the evidence behind investments that prevent and reduce violence while strengthening communities from the bottom-up. Next, it highlights five categories of federal policy recommendations designed to prevent and reduce violence:

To illustrate the viability of each recommendation, we also include examples of successfully implemented policy interventions. The blueprint concludes by recasting the affirmative vision for community safety.

There has been much confusion and conjecture regarding recent increases in crime rates. While staying true to the realities that shape public safety within communities, it is important to first acknowledge that crime rates are imperfect measurements of safety. This is, in part, because most crime is never reported, not all police departments report crimes to the federal government, and the kinds of crimes that police track and report are only a small subset of certain categories of crime.

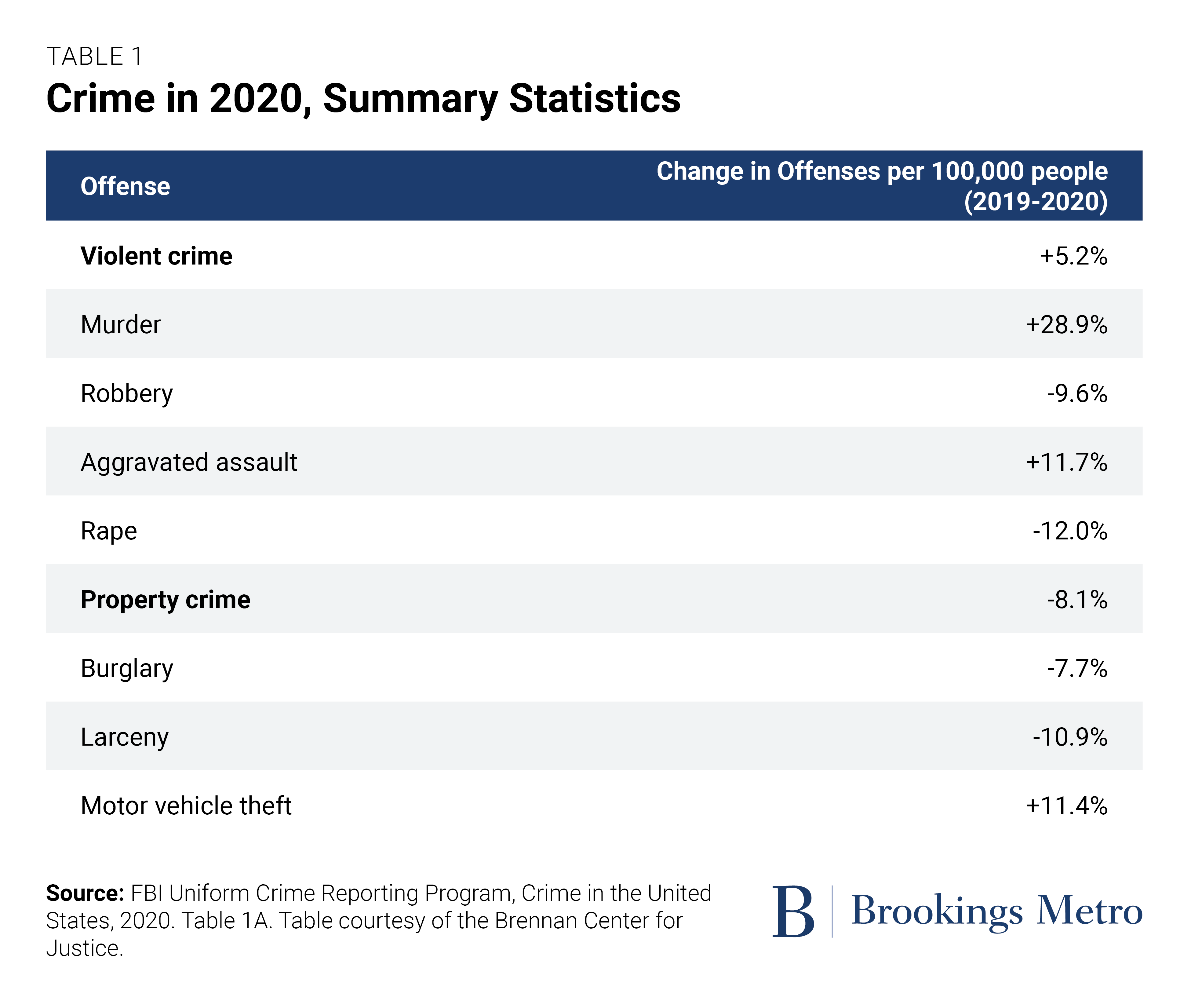

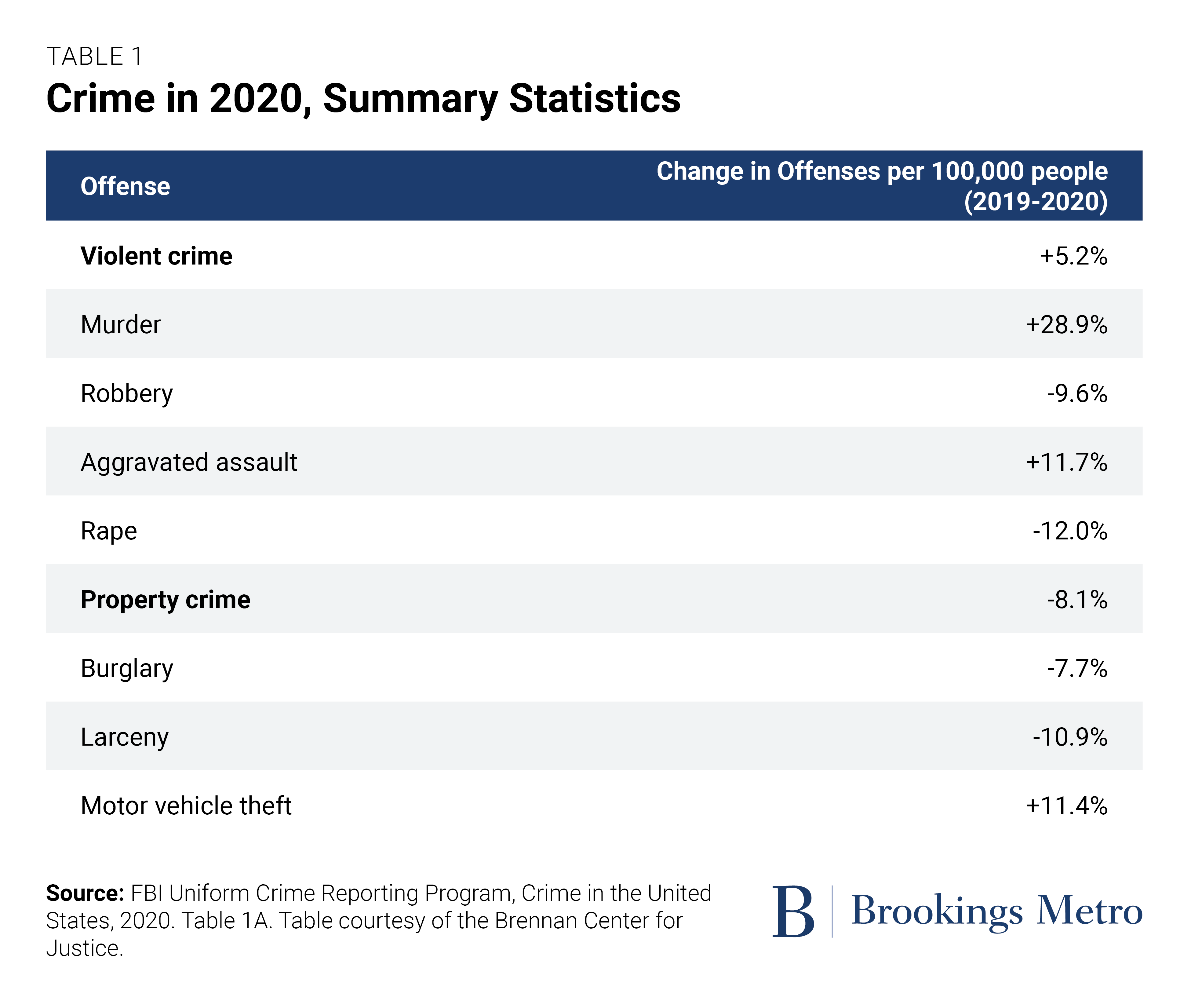

That being said, police-reported crime rates may provide a snapshot of broad trends. And in looking at these trends, several points become clear. First, the data suggests that the national murder rate increased by nearly 30% during 2020—a phenomenon that occurred in red and blue places and rural and urban areas alike. However, as Table 1 shows, these increases were not uniform across all types of crime. Indeed, many other forms of crime—including property crime, burglary, and robbery—were significantly down. Luckily, early data indicates that increases in violence appeared to slow in 2021.

Second, the rate of murder—the type of “violent crime” that increased the most—remains higher than other comparable countries, but well below historic levels in the United States from the 1980s and 1990s.

Third, while violence has been dispersed across the nation (urban and rural, red and blue), violence is geographically concentrated within cities—in specific neighborhoods, or even sets of streets within neighborhoods. In particular, communities affected by disinvestment and racial segregation have borne the brunt of violent crime increases, consistent with long-standing research surrounding the spatial concentration of violence. Meanwhile, more affluent areas have had near-record-low levels of murder.

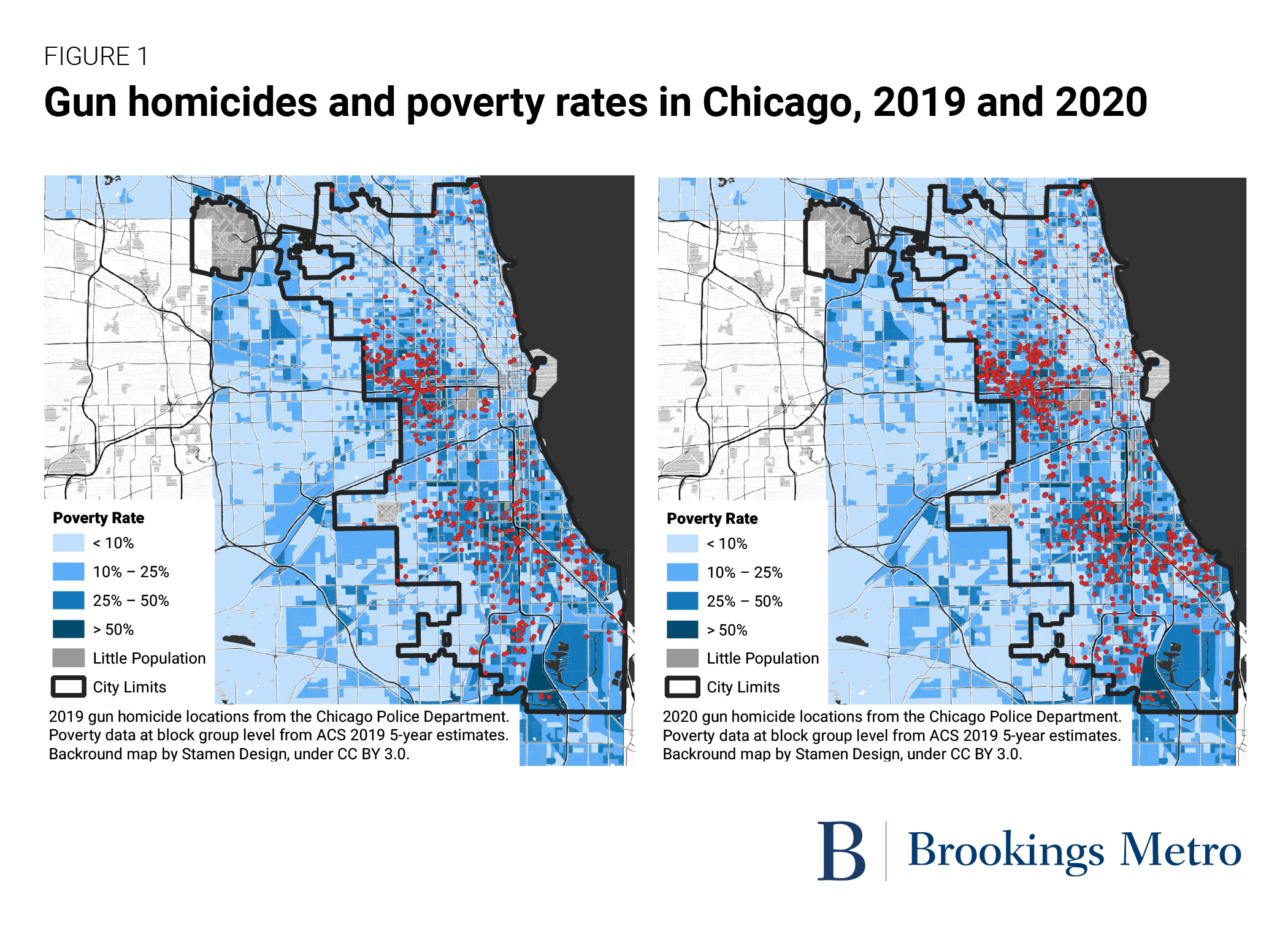

Figure 1 shows how these patterns appear in Chicago, where, between 2019 and 2020, gun homicide increases were concentrated in the predominantly Black and brown West, South, and Southwest neighborhoods that have long had high levels of gun violence alongside cycles of disinvestment, including historical redlining and present-day bank lending disparities.

The concentration of violence in disinvested Chicago neighborhoods mirrors other major cities, including Baltimore, Kansas City, Nashville, Tenn., and 13 additional cities for which data on violence outcomes and economic segregation is available. In short, this research underscores that community safety is deeply connected to neighborhood conditions produced by public and private sector disinvestment, particularly in regard to residents’ access to economic opportunity, quality education, stable housing, and health care.

The intersection between place, safety, and opportunity reflects long-standing challenges in America—but also a chance to reconsider how the federal government advances public safety policies. These challenges call for creative, thoughtful responses that center evidence-based investments in communities, rather than backsliding into harshly punitive policies.

Five categories of evidence-based investments are proven to not only prevent and reduce violence and harm, but also address patterns of geographic inequity that fuel violence and harm in the first place. In this section, we present the evidence on these investments before pivoting to policy recommendations backed by such evidence.

A public health approach to preventing violence can address the structural factors that increase susceptibility to violence, while advancing protective environments that nurture safety, health, and well-being. Areas of investment that are backed by the research evidence include:

Neighborhoods with higher poverty, unemployment, and income inequality rates have higher rates of violent crime. But the directionality goes both ways: Evidence demonstrates that by enhancing economic opportunity and reducing segregation within neighborhoods, communities can improve safety outcomes.

Investing in youth—whether through school programs, early childhood programs, mentorship, or other interventions—is one of the most impactful ways that policymakers can support long-term community safety. Indeed, research identifies “emerging adulthood” as a critical time to intervene positively to prevent future violence and increased criminal-legal involvement over a lifetime.

Given the spatial concentration of violence within cities and towns, strategies focused on alleviating neighborhood distress can significantly reduce crime. Research indicates that by implementing built environment improvements—including fixing abandoned buildings, increasing access to parks, and improving lighting and other aspects of the public realm—cities and towns can significantly reduce violence.

Nearly every community-based safety intervention outlined in this brief requires the leadership of community-based organizations. These organizations have long been testing alternative, bottom-up solutions to safety—especially in disinvested neighborhoods. However, the community infrastructure and institutions needed to stabilize communities are routinely underfunded.

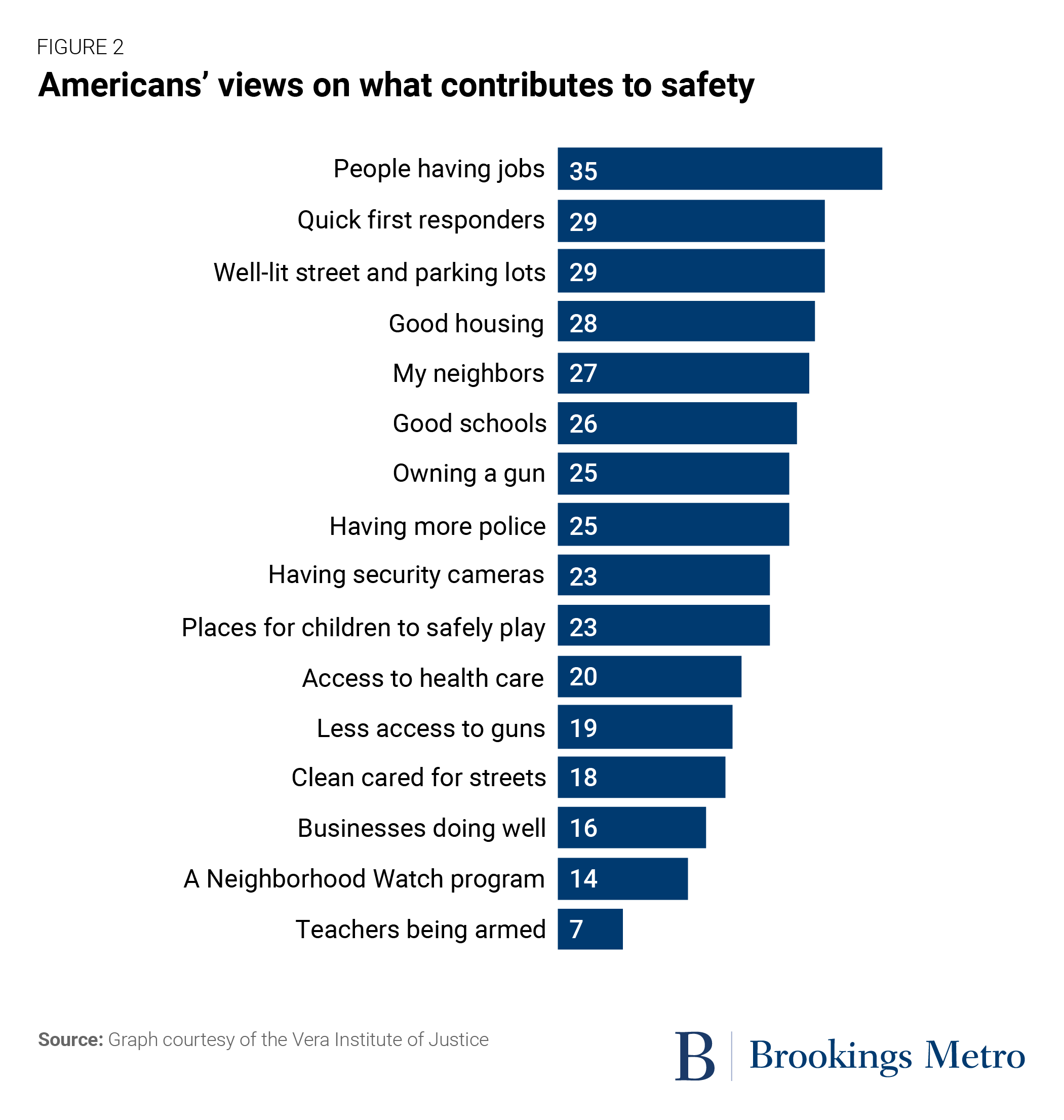

Across all five categories above, each community safety intervention is not only backed by research; each is also supported by public opinion. The Vera Institute of Justice recently conducted a national poll of 4,000 voters spanning the political spectrum, oversampling in the most politically diverse states. The results, presented in Figure 2, show that jobs, housing, community infrastructure, and schools are the top factors when asked what contributes to safety.

These findings are consistent with other survey data, such as a recent Alliance for Safety and Justice national survey of crime survivors, which found that 60% of survivors prefer prevention and rehabilitation as opposed to punishment. Taken together, these results indicate that public opinion is shifting in a direction that follows the evidence: Americans increasingly prefer preventative safety investments that work—such as jobs, housing, and community investment—over punitive approaches.

The federal government has a critical opportunity to follow this evidence and enact policies aimed at stopping violence and harm before they happen. In particular, the federal government can leverage its capacity as a funder to enable innovative pilots, scale successful interventions, and utilize its interagency expertise to provide guidance and evaluation support. The following section offers 16 evidence-based policy recommendations that are aligned with this vision, organized by the categories of evidence explained above.

1. Create sustainable funding streams for community violence intervention programs: The federal government could more effectively prevent violence by creating long-term funding streams that support evidence-based community violence intervention (CVI) programs—both the hospital-based and community-centered models. Many CVI models have expanded in the past year, largely by leveraging flexible “fiscal recovery funds” in the American Rescue Plan (detailed further in this Civil Rights Corps guide). However, in a recent Brookings report, CVI practitioners expressed concerns about how they can continue their life-saving violence interruption work after those dollars are spent. Moreover, other studies indicate that ARP funds have predominantly not been used for these purposes, comprising only 0.14% of the first funding tranche. In short, Congress should prioritize targeted and dedicated investments in these programs, as well as continual and long-term investments that are more than sporadic reactions to violence upticks. While the Biden administration has proposed $500 million for CVI in its FY23 budget, this request is still far less than needed to meet existing demand.

The federal government could advance CVI priorities in a few ways. It could fulfill the White House FY23 CVI budget request and bolster existing funds (such as the Preventing Violence Affecting Young Lives grant) that are already providing critical dollars for this work. To meet growing demand and ensure that violence interrupters are paid living wages that allow them to continue their work, the government should also build targeted, sustainable, and robust CVI funding streams overseen by the Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) rather than the Department of Justice. Making this administrative switch underscores the fact that the HHS has the employees, resources, and institutional orientation necessary to expand CVI programs reflective of the public health approach to safety so key to effective violence prevention.

Case study: Trauma Recovery Center Network (Ohio)

In 2017, Ohio allocated $2.6 million of its Victims of Crime Act (VOCA) funding to create a Trauma Recovery Center Network, which helped hospitals and community-based organizations provide wraparound services to traditionally underserved victims (including victims of gun violence) with supports such as short-term safe housing, legal advocacy, substance use treatment, mental health counseling, and essentials like food and clothing. Then attorney general and current Republican Governor Mike DeWine made Ohio the second state in the nation to adopt this model (after California in 2001), and current Attorney General Dave Yost has grown it so that Ohio has the second-highest number of trauma recovery centers in the nation. According to the Alliance for Safety and Justice, trauma recovery centers are both treatment- and cost-effective models for reaching underserved crime victims such as people experiencing street violence, younger victims, people who are homeless, LGBTQ+ victims, and communities of color. There are now more than 40 trauma recovery centers across the country.

2. Scale civilian crisis response models: Given promising early outcome data from civilian crisis response models in places such as Oregon and Denver, the federal government should consider providing competitive grants to scale these models nationwide while embedding an evaluation component to further measure the associated success and cost savings. In designing grants, Congress should take care to not only prioritize crisis response models that provide an alternative to low-level offenses (such as substance use or homelessness), but also include models that address intimate partner violence—another area where trained professionals can avoid a substantial amount of harm and criminal-legal entanglement. While the federal government has made significant strides in improving crisis response supports—including through the new Suicide and Crisis Lifeline, 988, and its Qualifying Community-Based Mobile Crisis Intervention Services program—establishing more targeted grants could help jurisdictions pilot and scale the most successful of these non-carceral models while expanding the evidence base on what works.

Case study: Person in Crisis Team (Rochester, N.Y.)

In September 2020, Rochester, N.Y. created a new Office of Crisis Intervention Services, housed within the Department of Recreation and Human Services, to be a non-law-enforcement, comprehensive community response to homicides, domestic violence, and mental health crises. The office was funded by the transfer of $681,100 from the Rochester Police Department’s budget and $300,000 from the city’s Contingency Budget. In January 2021, the office launched the Person in Crisis (PIC) Team to divert mental health calls and connect residents in crisis with social workers trained in emergency response. To access the PIC Team, residents call “211” instead of “911.” Calls are routed through the Goodwill of the Finger Lakes 211 Life Line call center to provide a 24/7 response to residents of all Rochester ZIP codes. Monthly service reporting and outcomes can be found here.

3. Increase funding for community health clinics, trauma recovery centers, and community health workers: Given the extensive evidence on how health care and treatment access can significantly reduce crime, the federal government should consider increasing funding for clinics, community health workers, and training and workforce development for health care professionals—particularly in lower-income census tracts. There are many vehicles through which they could do so, including: